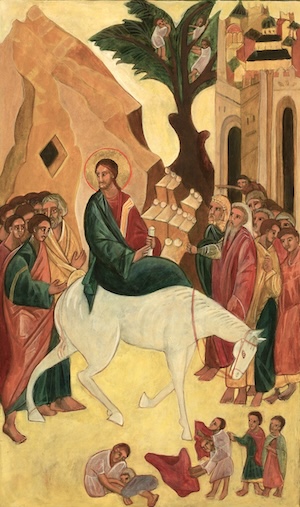

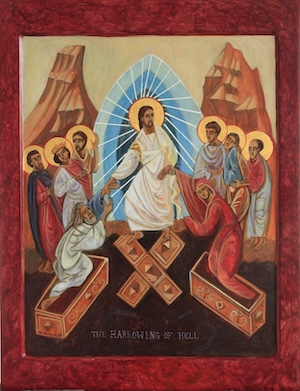

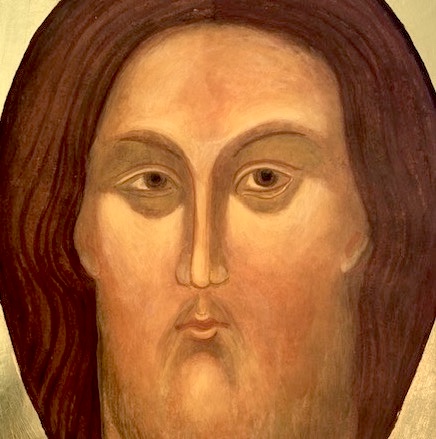

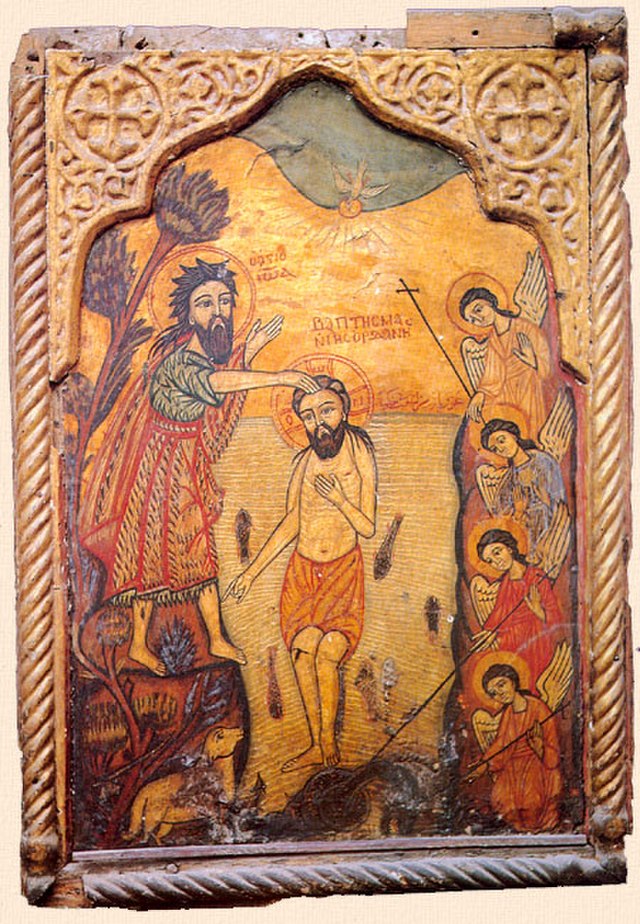

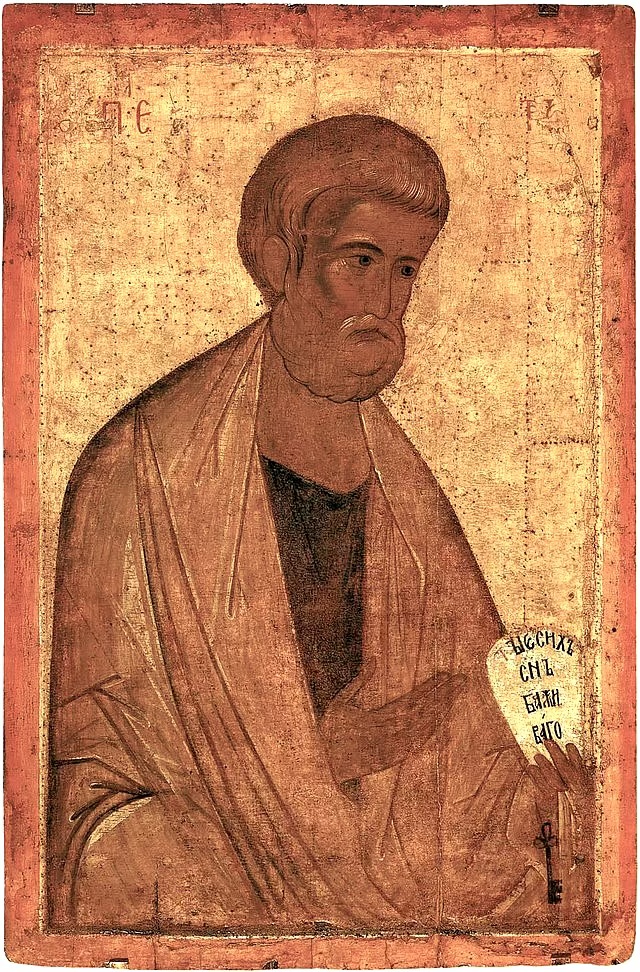

If ever there were icons that personified the phrase, “Icons as theology in Color” it would be Lenten and Easter Icons.

We could start with the Stations of the Cross Icons.

I wrote these icons many years ago in a small village in the Hudson Valley New York. I had been asked by my priest at the beginning of Lent to write these icons and have them finished by Good Friday!!! Those of you who have written icons know how impossible a task that seemed! And so it was, that I embarked on that somber and deep journey of walking with Christ as I created each icon with prayer and sometimes tears. I do want to mention that I was studying icon writing at that time with a nun at the New Skete Monastery in upstate New York, Sister Patricia Reed. When I would go up to work with her, I often watched her as she created her Stations of the Cross icons for the All Saints Cathedral in Albany New York. So, I asked for her help and she kindly gave me color photographs of her stations, which I used to create these icons here. That was a big help, and it is part of the traditions of icon writing, that the designs are handed down from generation to generation, from teacher to pupil, thus ensuring a correct understanding and transmitting the means and methods of icon writing from master to student.

These currently hang in the chapel of the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Saint Petersburg, Florida. The tradition of walking the path of Christ’s Passion dates back to the earliest Christian pilgrims, who visited the sites in Jerusalem believed to be where Jesus walked to his crucifixion. By the 13th and 14th centuries, the Franciscans—who had been granted custody of Christian holy places—popularized this devotion in Europe by constructing “stations” that mirrored the Via Dolorosa. Over time, different numbers of stations were used, until Pope Clement XII fixed the total at fourteen in 1731.

During the late Middle Ages, devotion to the Stations of the Cross was tied to the idea of indulgences, leading some Protestants to reject the practice. Nonetheless, Francis of Assisi and his order played a pivotal role in promoting veneration of Christ’s Passion, establishing shrines and receiving papal recognition as custodians of the holy sites. By the 15th and 16th centuries, the Franciscans built outdoor Stations of the Cross across Europe, often placing them in small chapels or along paths leading to churches.

The titles of each Station, and the Scripture relating to it are as follows:

Station One. The accusing hand condemns Jesus to crucifixion. Matthew 27:31

Station Two. Jesus Picks up His cross. The strong diagonals give a powerful sense of unrest, explosive energy. John 19:6

Station Three. Jesus Falls For the First Time from the weight of the Cross. John 19: 1-3

Station Four. Jesus Meets His Blessed Mother. Luke 2: 34-36 …and a sword shall pierce your heart…

Station Five. The Cross is laid on Simon of Cyrene. Luke 23:26-27. Bent over double, the cross almost crushes Jesus.

Station Six Saint Veronica wipes the face of Jesus. Isaiah 53:2-3

Station Seven: Jesus Falls for the Second Time This time the diagonal of the cross is pointing forward- this is the halfway point of the Passion

Station Eight: The Women of Jerusalem mourn our Lord Luke 23:28-29

Station Nine: Jesus Falls for the Third Time. Isaiah 53:4-6

Station Ten: Jesus is Stripped of His Garments. Luke 23: 34-35

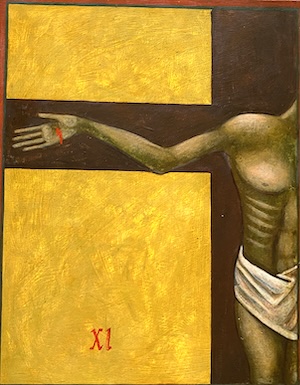

Station Eleven : Jesus is nailed to the Cross. Luke 23:33

Station Twelve: Jesus Dies On The Cross Luke 23:44-47. Into your hands I commend my spirit… The rectangle is broken- split apart, showing visually the magnitude of this event forever changes the world.

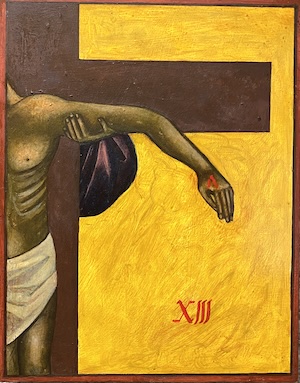

Station Thirteen: Jesus is Taken Down from the Cross. Matthew 27: 54-55. The position of the hand shows that he is dead.

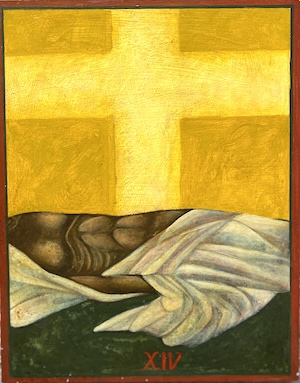

Station Fourteen: Jesus is Laid in the Tomb. Matthew 27:59-62

With these, you may notice that no faces are visible, and the flesh color is neither white, black or any particular ethnicity. This is because these icons are meant to be a universal visual language to be “read” and related to by all humans, because God’s plan is to save all people.

Some other of my icons that relate to Lent and Easter that are also currently at the Cathedral of Saint Peter- until after May 1, are :

Thinking about the Cross and Icons, I came across this writing of St. Theodore the Studite, an Abbot in a monastery in Bithynia in the late 800’s: “THE CROSS AND THE ICON. “Should the cross be venerated more than the icon?” the heretics ask. “Should it be venerated equally, or in a lesser degree?”

“Since there is a natural order in these things, I think you are speaking superfluously. If by ‘the cross’ you mean the original cross, how could it not have priority in veneration? For on it, the impassable Word suffered, and it has such power that by its mere shadow it burns up the demons and drives them far away from those who bear its seal. But if you mean the representation of the cross, your question is not intelligent. The effects receive differing honor just as much as the causes differ, since whatever is received for some use is less honored than that for the sake of which it was received. Thus the cross is received for the sake of Christ, because it was formerly an instrument of condemnation, but was later hallowed, when it was accepted for the use of the divine passion.” St. Theodore the Studite, On The Holy Icons.

Having just given a talk and written an article attempting to explain the period of iconoclasm, I include the above quote as an eloquent explanation not only of the veneration of the Cross, but also of the obvious distinctions between veneration due to the original source and that due a replication of it.

I’ll close this month’s blog with a prayer and a blessing for God to bless each of you especially during this Holy Season of Lent and Easter:

“Gracious Father, whose blessed Son Jesus Christ came down from heaven to be the true bread which gives life to the world; Evermore give us this bread, that He may live in us, and we in him; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, One God, now and forever. Amen.” From the Book of Common Prayer.

With love and prayers,

Christine Hales

Some Interesting Links for Iconographers

Sacred Geometry with Donald Duck! A fun explanation for beginners

Interview with Todor Mitrovic, Orthodox Arts Journal

Christian Iconography Shows Us the Pattern of Reality: Jonathan Pageau, St. Tikhon’s Seminary

My Links:

LINKS For Christine Simoneau Hales 2025

- https://newchristianicions.com my main website

- Https://christinehalesicons.com Prints of my Icons

- https://online.iconwritingclasses.com my online pre-recorded icon writing classes

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK2WoRDiPivGtz2aw61FQXA My YouTube Channel

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristineHalesFineArt or https://www.facebook.com/NewChristianIcons/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christinehalesicons/?hl=en

- American Association of Iconographers: FB Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/371054416651983

American Association of Iconographers Website: https://americanassociationoficonographers.com