Embracing the Light of New Possibilities

Happy New Year! It’s a time for new beginnings, a chance to refresh our minds, hearts and spirits, a time to reevaluate our goals and plans in light of a change of perspective.

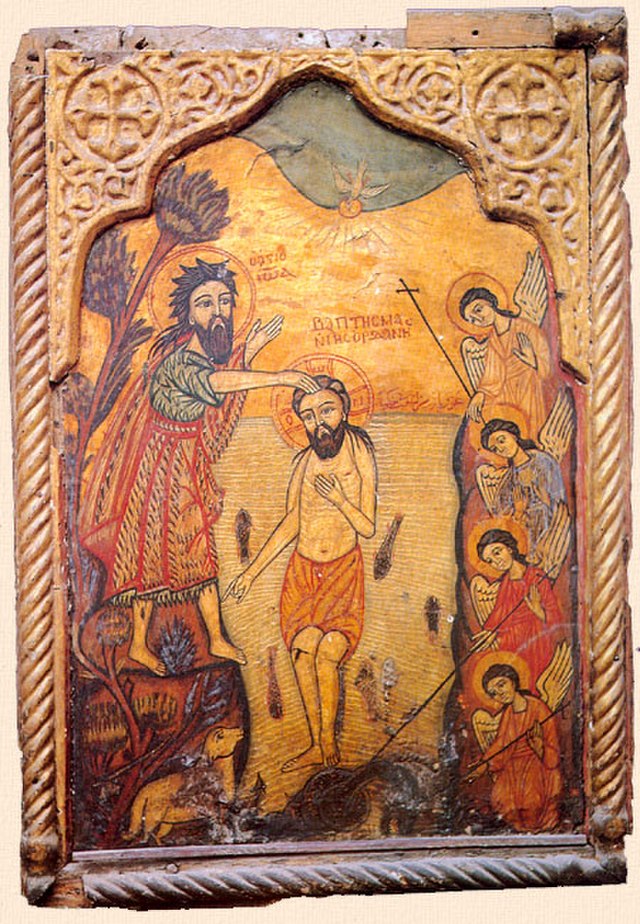

The Eastern branch of the Church originally celebrated Epiphany as the Baptism of Jesus as early as 200AD. In the Western Church, gradually the appearance of the three kings at the nativity of Christ’s birth and the wedding feast of Cana were additionally associated with Epiphany.

Thinking about all this, it seems to me that each of those Holy events signifies a time of new beginnings. The three kings came to honor a newborn king- the beginning of a radical shift in the world’s perspective on sin, freedom, and God.

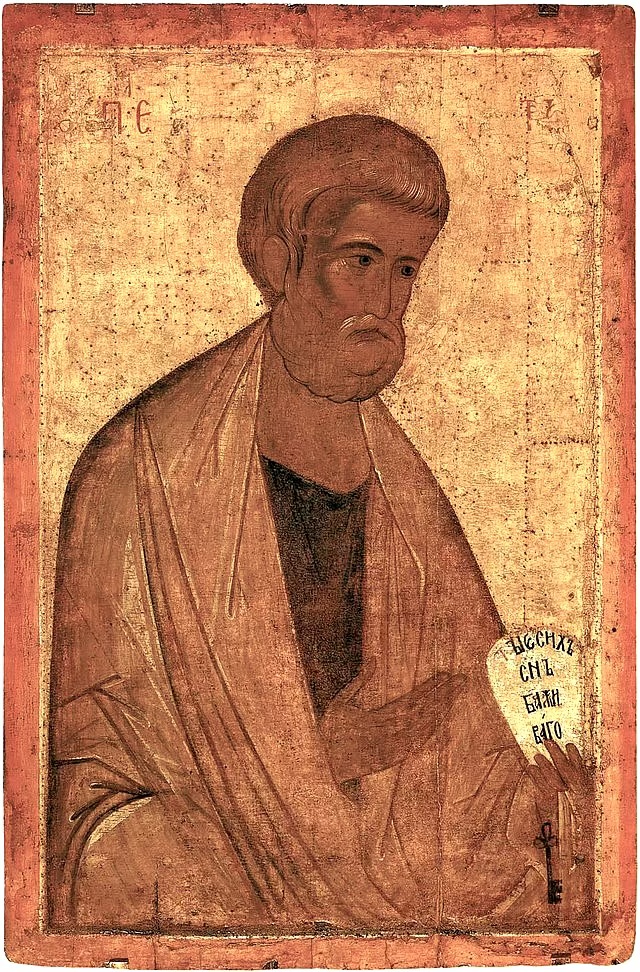

The Baptism of Jesus occurred when he was in his early thirties and signified his great humility in identifying himself as human. At the same event, God’s voice declared Jesus to be His son, in whom he is well pleased. This was the first public demonstration of both Jesus’ humanity and divinity and serves as an example for us to follow. It is for us to be humble, asking for God’s blessing at Baptism and eagerly listening to every word that comes from the Father.

Jesus said, ‘Out of your heart shall flow rivers of living water’. John 7:38

The wedding of Cana was the first manifestation of the miraculous marking the beginning of the miraculous ministry of Jesus. How do we enter into this ancient mystery? We might remember that when God is asked for help, He can turn even ordinary facts of reality – no wine left- into the extraordinary fulfillment of desires and needs.

“Since the creation of the world the invisible things of God are clearly seen by means of images. We see images in the creation which, although they are only dim lights, still remind us of God.” John of Damascus

And so, at this time of new beginnings, a New Year, let us contemplate how this feast day can affect our icon writing practice. Any of the three aspects of Epiphany can be used to strengthen and inspire our practice in multiple ways. Keeping a spiritual journal and recording our thoughts and drawings can make our work a process of sanctification. Sanctification is a Christian concept that refers to the process of becoming holy or sacred, or being set apart for a special purpose. It is a gradual process of spiritual growth and transformation that involves effort, commitment, and personal sacrifice.

Sanctification is a gift from God to those he loves, and is a result of grace.

Happy New Year!

The arrival of a new year often brings a sense of anticipation and hope—a time to refresh our minds, hearts, and spirits. It is a moment for reevaluating our goals, plans, and perspectives, and for embracing the potential of new beginnings.

In the Christian liturgical calendar, Epiphany—celebrated on January 6th—marks a significant point in the journey of faith. This feast day invites us to reflect on profound moments of revelation, transformation, and divine manifestation. As we step into a new year, it’s an opportunity to consider how these themes of new beginnings can inspire and strengthen our own spiritual practices, particularly in the art of icon writing.

The Significance of Epiphany

Epiphany is traditionally a feast that celebrates the revelation of Christ to the world. The Eastern branch of the Church originally recognized Epiphany as the celebration of Jesus’ Baptism in the Jordan River, dating back to as early as 200 AD. Meanwhile, in the Western Church, the focus gradually expanded to include the visit of the three kings (the Magi) to the newborn Christ and the wedding feast at Cana, marking the first public miracle of Jesus.

What unites these events is their profound symbolism of new beginnings.

- The Visit of the Three Kings: The Magi came to honor the newborn king, an event that marked a radical shift in the world’s perspective on sin, freedom, and God’s plan for salvation. Their journey was not just one of homage, but also a declaration of the start of a new era in the world’s understanding of the divine.

- The Baptism of Jesus: At around thirty years old, Jesus underwent baptism, not because He needed it, but to demonstrate His profound humility and identification with humanity. In this moment, God’s voice declared, “This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17). It was a public affirmation of both Jesus’ humanity and divinity, setting an example for us all to follow—humility, obedience, and openness to God’s will.

- The Wedding at Cana: The first of Jesus’ miracles, turning water into wine at a wedding feast, was the beginning of His miraculous ministry. It shows how, when we seek God’s help, He can transform even the most ordinary situations into extraordinary ones, fulfilling desires and needs in ways we may not expect.

New Beginnings: The Call to Sanctification

When we consider the events of Epiphany—the kings, the baptism, and the miracle at Cana—we are reminded that new beginnings come with new insights, new possibilities, and the potential for transformation. These moments of revelation can serve as inspiration for our own lives, particularly in how we approach our spiritual practices.

One practice that can particularly benefit from these reflections is the art of icon writing. For those of us who engage in this sacred work, Epiphany offers an invitation to approach our iconography with a renewed sense of purpose and devotion.

The Role of Sanctification in Our Work

Sanctification is a Christian concept that refers to the process of becoming holy, or being set apart for a special purpose. It involves spiritual growth, effort, commitment, and sacrifice, and ultimately results from God’s grace. As we enter this time of new beginnings, Epiphany provides us with the perfect context to view our work—not just as art, but as an act of sanctification.

In the icon writing tradition, the creation of sacred images is not merely an artistic endeavor. It is a spiritual practice—a way of deepening our relationship with God and of participating in the divine work of revealing God to the world. As we create, we invite God’s grace into our work, and we seek His discernment and guidance.

Practical Ways to Embrace Epiphany in Icon Writing

- Keep a Spiritual Journal: Epiphany is an ideal time to begin—or renew—a spiritual journal. Write down your reflections on the feast day, your thoughts on the new year, and any drawings or sketches that come to mind. Let this journal be a space for contemplation and prayer as you reflect on the mysteries of God’s revelation.

- Approach Your Icon Writing as a Process of Sanctification: Remember that icon writing is not just about technique, but also about the transformation of the soul. Let the process itself be one of spiritual growth. Each stroke, each color, each detail can be offered up as a prayer for God’s blessing and guidance.

- Draw Inspiration from the Three Aspects of Epiphany: Whether you focus on the humility of the Baptism, the honor of the Magi’s visit, or the miraculous transformation at Cana, let these themes inspire your work. Ask yourself how each event relates to your journey and how it can be expressed through your icons.

- Seek God’s Blessing and Discernment: Just as Jesus humbly sought the Father’s blessing at His Baptism, approach your work with a similar humility. Ask for God’s guidance and discernment as you create, and trust that He will equip you with the skill and insight to faithfully depict His Holy Word in visual form.

A Prayer for the New Year

As we begin this new year, let us pray for the grace to approach every task, including our icon writing, as an act of sanctification. May we seek new beginnings in our spiritual lives, just as the three kings, the baptism of Christ, and the miracle at Cana brought about radical transformation. And may our work be filled with the light of Epiphany, bringing us closer to God and to the world’s deepest truths.

Epiphany is a beautiful time to celebrate new beginnings, clarity, and the light that guides us forward. Just as the wise men followed the star, we too are invited to follow our own paths of growth and transformation. May this Epiphany bring you fresh insight, new opportunities, and the courage to begin anew.

May God continue to bless the work of your hands with His gifts of discernment and skill, and may you experience the joy of new beginnings in your creative and spiritual journey through icon writing.

INTERESTING ICON LINKS:

Video with Metropolitan Kallistos Ware on Iconography: Doorway into Heaven (39 minutes)

Birch Panels suitable to gesso for icons: Trekell Art Supplies

Blessings,

Christine Simoneau Hales. New Christian Icons