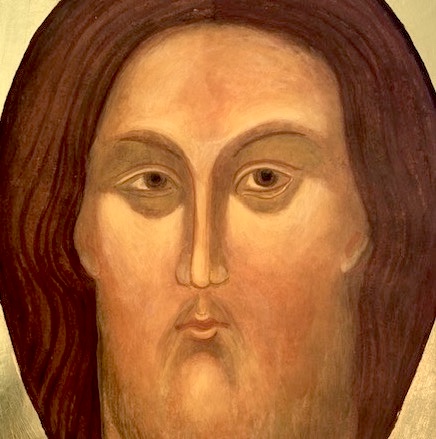

In the realm of Christian spirituality, icons stand as more than mere religious art. They are a visual form of divine communication, a sacred language that transcends time and culture. As Leonid Ouspensky notes, icons do not serve religion in a utilitarian sense but are an intrinsic part of it—one of the means through which believers encounter and commune with God. When I think of Icons as theology in color, I inevitably go to the Novgorod Icons which were created in Russia from the 14th to 17th centuries.

Icons as Liturgical Art

An icon, much like sacred scripture, is a vessel of divine revelation. In the same way that words in liturgy guide the faithful toward deeper understanding, icons serve as instruments of knowledge and communion with God. They are not decorations; they are theological expressions rendered in color and form, inviting contemplation and prayer.

Tradition and the Role of the Holy Spirit

Christian tradition is often misunderstood as mere adherence to historical customs, but its essence is far more profound. As stated in theological reflections, true Tradition is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church. It is through the Spirit that believers gain the faculty to perceive divine Truth—not merely through human reason but through the illumination of faith. Icons, shaped by this Tradition, bear witness to a spiritual reality that is ever-present and active.

The Power of Signs and Symbols

The material and spiritual worlds are not separate; rather, they are deeply intertwined. This is evident in the role of symbols, which serve as bridges between the seen and unseen. Early Christian symbols carried layers of meaning—the image of a saint in the catacombs could signify a soul in paradise, an embodiment of prayer, or even the Church itself. Through repeated sacred gestures and imagery, the faithful are invited to enter into the mystery of divine presence.

The Evolution of Christian Symbolism

Christianity has always expressed its mysteries through symbols. Early believers adapted existing signs from the surrounding world—such as the dove, peacock, and anchor—infusing them with new, transcendent meaning. As time passed, explicitly Christian symbols emerged, such as the fish (Ichthys) and the lamb, both representing Christ. These symbols, while rooted in human expression, point to eternal truths beyond words.

Icons: Transcendent Yet Concrete

While maintaining the depth of symbolic language, the icon introduces a unique dimension—the human element. Unlike abstract symbols, the icon makes divine mysteries visually accessible. It brings the infinite into finite form, allowing the ineffable to be expressed in a way that speaks directly to the soul. In the words of Egon Sendler, the icon transforms the abstract into something both transcendent and concrete, revealing the invisible through the visible.

Conclusion

Icons are not simply religious images; they are theology in color, sacred windows into the divine. Through tradition, symbolism, and the work of the Holy Spirit, they continue to guide believers into a deeper relationship with God. Whether through the gaze of a saint, the presence of Christ, or the gestures of the liturgy, icons remind us that the sacred is always near, calling us into communion with the eternal.

I hope this article has been not only food for thought, but helps to build a solid foundation of theology for contemporary icon development.

“So, my dear brothers and sisters, be strong and steady, always enthusiastic about the Lord’s work, for you know that nothing you do for the Lord is ever useless.” 1 Corinthians 15:58

Until next month. Blessings,

Christine Simoneau Hales, Iconographer

LINKS For Christine Simoneau Hales 2025

- https://newchristianicions.com my main website

- Https://christinehalesicons.com Prints of my Icons

- https://online.iconwritingclasses.com my online pre-recorded icon writing classes

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK2WoRDiPivGtz2aw61FQXA My YouTube Channel

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristineHalesFineArt or https://www.facebook.com/NewChristianIcons/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christinehalesicons/?hl=en

- American Association of Iconographers: FB Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/371054416651983

American Association of Iconographers Website: https://americanassociationoficonographers.com