Two Books That Open the Heart Through Icons and the Saints

In the world of Christian spirituality, a beautiful mystery unfolds whenever art and prayer meet. Two icon related books—The Dwelling of the Light: Praying With Icons of Christ by Dr. Rowan Williams, and The Song of Saints: Celebrating the Saints with Anglican Prayer Beads by Catherine Gotschall—offer readers rich opportunities to encounter that mystery with depth and devotion. Though very different in scope, each invites us to slow down, to look more deeply, and to let the Holy Spirit reshape how we see God, the world, and ourselves.

Seeing Christ Anew: Rowan Williams on Praying With Icons

When The Dwelling of the Light was first published in 2003, Dr. Rowan Williams had just begun his tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury. Already a respected theologian and scholar, Williams offered the world a slim but luminous volume on praying with icons of Christ. It remains one of his most beloved spiritual works.

At the heart of the book lies a profound reverence for icons—not as decorative artifacts, but as encounters with divine presence. Williams writes:

“In their presence you become aware that you are present to God and that God is working on you by his grace, as he does in the lives and words of holy people.”

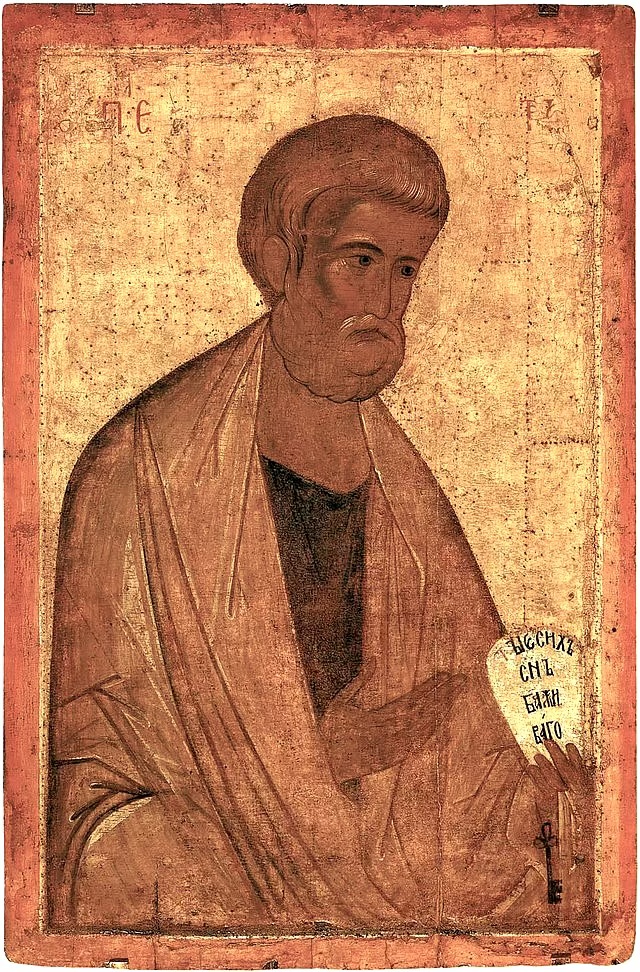

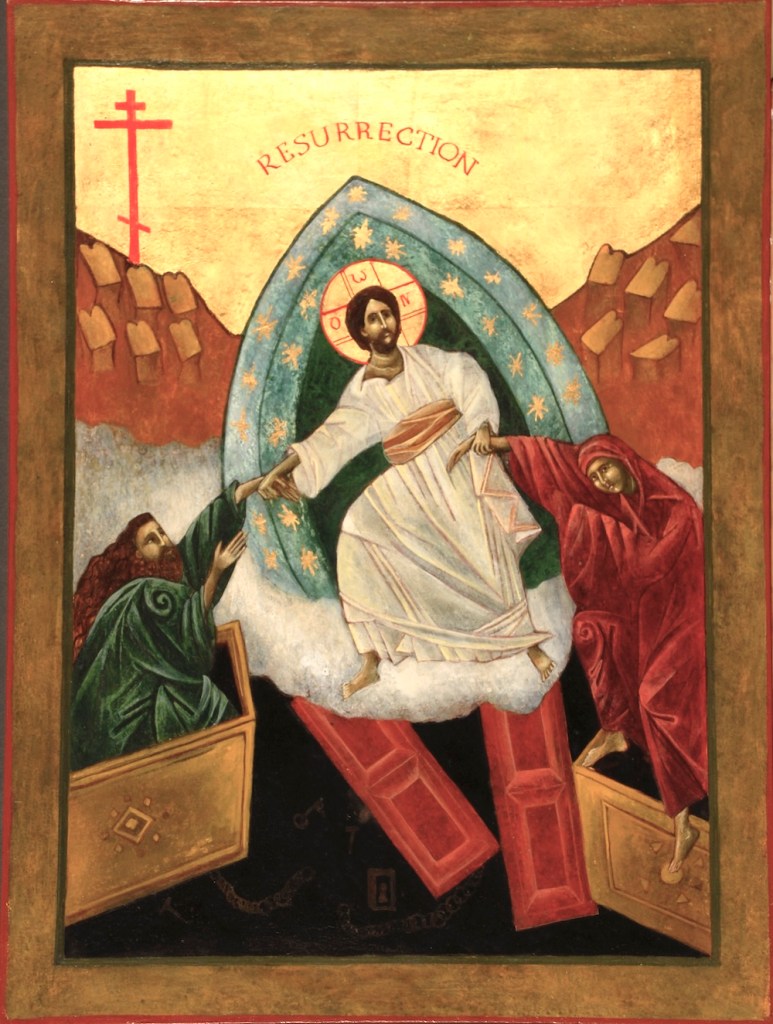

Using four deeply significant icons—The Transfiguration, The Resurrection, The Hospitality of Abraham, and Christ Pantocrator—he guides the reader into a prayerful way of seeing. Icons, he suggests, are not depictions of a moment frozen in history; they reveal a life “radiating the light and force of God.”

In Williams’ hands, each icon becomes not only an image but a doorway: a way for Christ’s transfiguring presence to shape our own vision of the world. The book is small enough to read in an afternoon but expansive enough to ponder for years.

I have always appreciated Dr. Williams’ viewpoint on icons and sacramentals in the Anglican Church. Sometimes on my lunch break I like to pick up one of his books for some quick inspiration!

Williams wrote a companion volume a year earlier—Ponder These Things: Praying With Icons of the Virgin (Canterbury Press, 2002)—which offers a similar depth of prayer through icons of Mary.

Related Links

• Image Journal: Conversation with Rowan William

• Author Page with additional works by Dr. Williams

Praying With the Cloud of Witnesses: Catherine Gotschall’s The Song of Saints

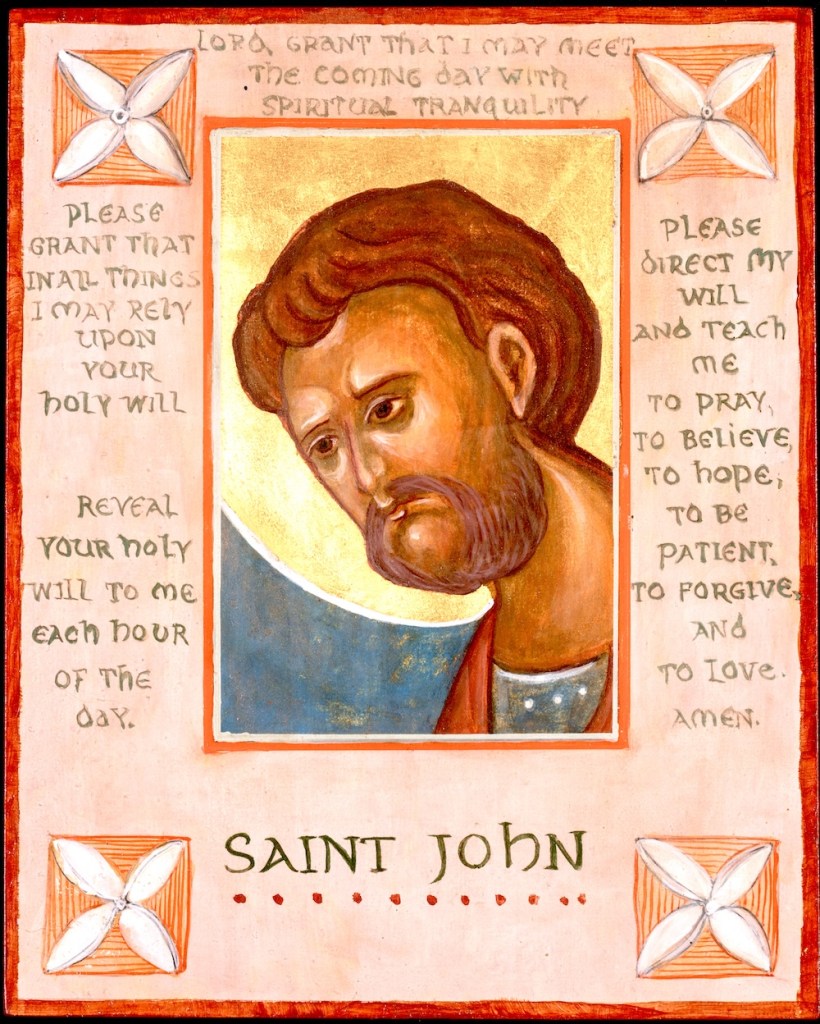

While Williams leads us to contemplate the face of Christ, Catherine Gotschall invites us to pray with the saints themselves. A lifelong Episcopalian, Gotschall has created an extraordinary resource in The Song of Saints: Celebrating the Saints with Anglican Prayer Beads.

I met Catherine at the Episcopal Convention of South West Florida several weeks ago and want to share this interesting book with you all since first class books on the lives of the saints are hard to come by!

Her book presents the lives of more than fifty saints from across the centuries—men and women whose faithful witness continues to echo through Christian history. Arranged within the six cycles of the liturgical year, the saints span the 1st to the 20th century and represent Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant traditions.

But what makes the book truly distinctive is its prayer practice. For each saint, Gotschall offers:

- A brief biography

- Prayers drawn from the saint’s own writings—letters, sermons, and vitae

- A way of praying these words with Anglican prayer beads

She describes a saint as:

“someone who has led a sacramental life… an outward and visible sign of deep and abiding inner spiritual grace.”

This is more than a book of history or devotional snippets—it is a tool for moving devotion “from head to heart.” Through the rhythm of the beads and the wisdom of the saints, readers are invited into a lived experience of prayer that feels both ancient and deeply personal.

Link to Purchase Book on Amazon

Art, Prayer, and the Ever-Living Presence of God

Together, these two books remind us of something essential: authentic Christian prayer is not an escape from the world but a way of seeing it more truthfully. Icons illuminate the radiant presence of Christ at the center of all things. The saints show us what life looks like when that presence is welcomed, trusted, and lived boldly across centuries and cultures.

Whether you are drawn to the serene gaze of Christ Pantocrator or to the stirring witness of those who followed him, these works offer gentle, profound companions for the spiritual journey.

They invite us—quietly but insistently—to ponder, to pray, and to be transformed.

Until next month, be blessed and be a blessing! And don’t forget, if you write an informative article about your icons or icon related information, please email me with your ideas and proposals. It would be wonderful to have articles written by more of you!

Love and prayers,

Christine Hales

Recent Posts on Saints; Stories of Saints and Icons and

My Next in- Person Icon Writing Retreats for 2026

LINKS For Christine Simoneau Hales 2025

- https://newchristianicions.com my main website

- Https://christinehalesicons.com Prints of my Icons

- https://online.iconwritingclasses.com my online pre-recorded icon writing classes

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK2WoRDiPivGtz2aw61FQXA My YouTube Channel

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristineHalesFineArt or https://www.facebook.com/NewChristianIcons/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christinehalesicons/?hl=en

- American Association of Iconographers: FB Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/371054416651983

American Association of Iconographers Website: https://americanassociationoficonographers.com

Contact Christine: chales@halesart.com