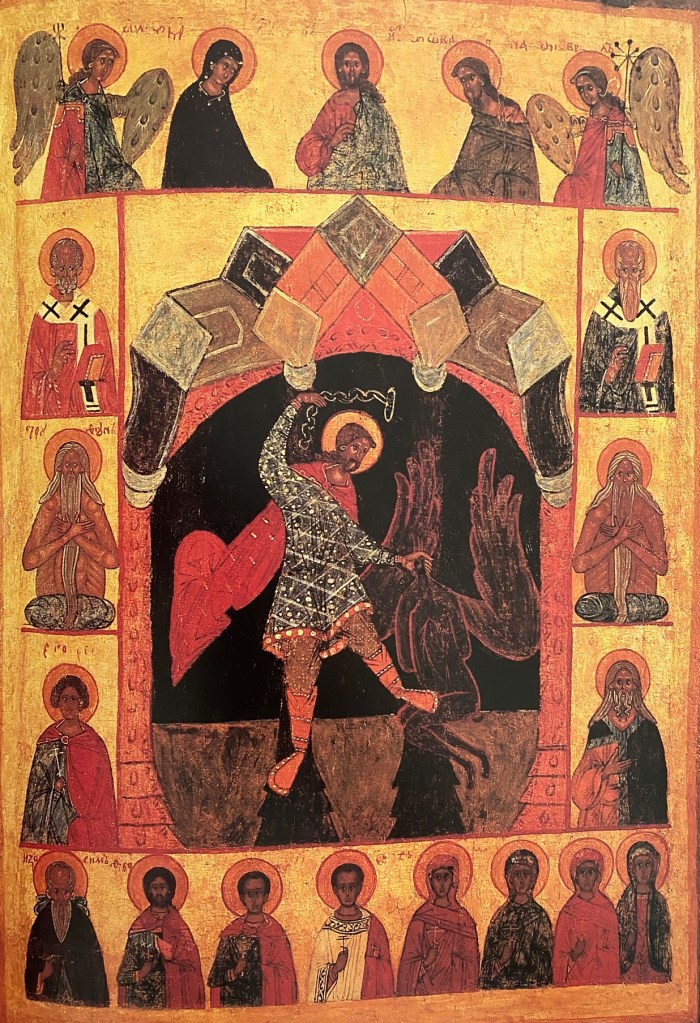

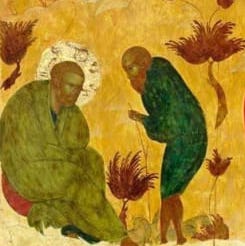

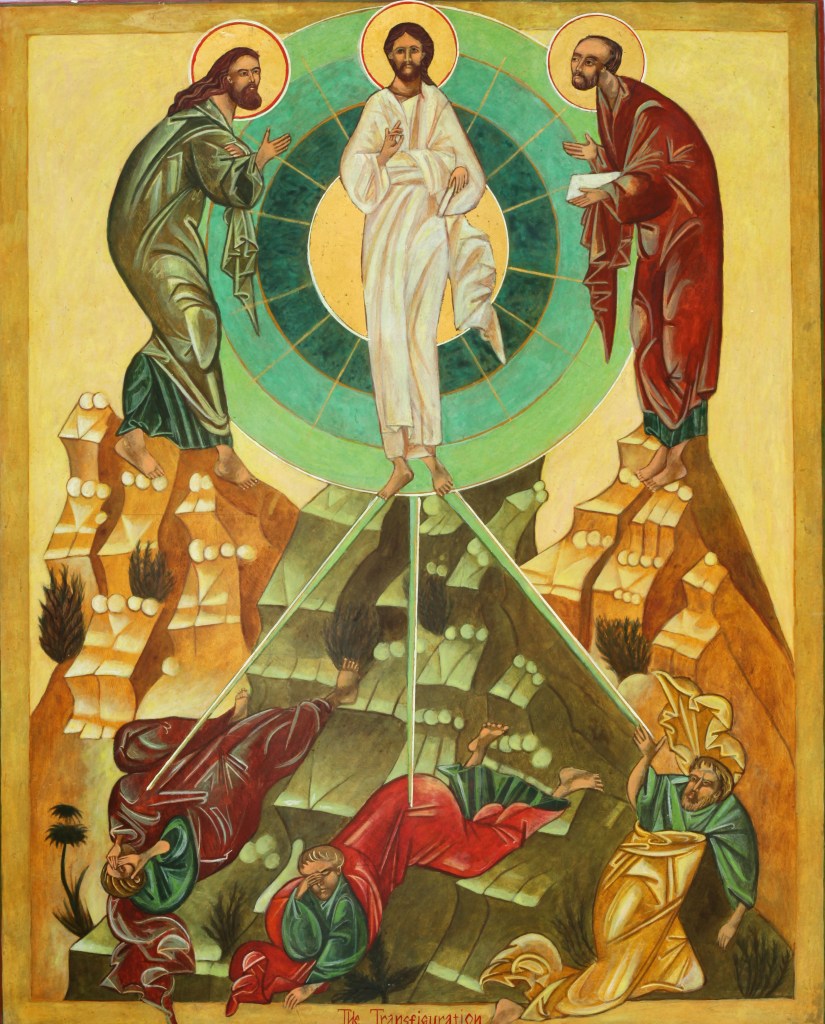

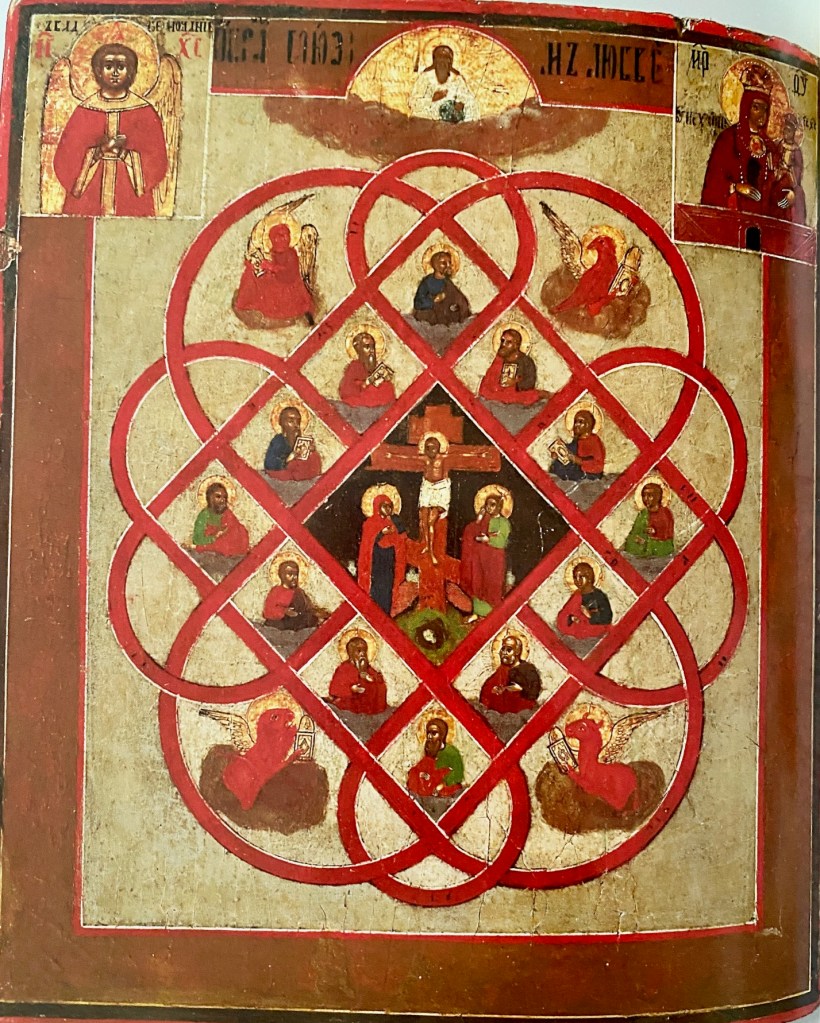

Innovation and change- not two words one usually associates with Iconography! But in order to have authentic icons today, they need to be able to relate to our culture today as well as to be expressions of our relationship to God today. In the words of a noted Romanian iconographer today, Todor Mitrovic, “…it is impossible to create authentic ecclesiastical art if we do not engage in a dialogue with contemporary art .

Last Supper, Todor Mitrovic

Of course, what that dialogue looks like visually, when translated through the filter of Byzantine Iconography, will look different for each iconographer. And this is right and correct, for each of us are products of different countries and cultures, but one faith. Our faith is what provides unity in our efforts to serve God with the talents He has blessed us with.

Take Giotto, As an Early Innovator Example

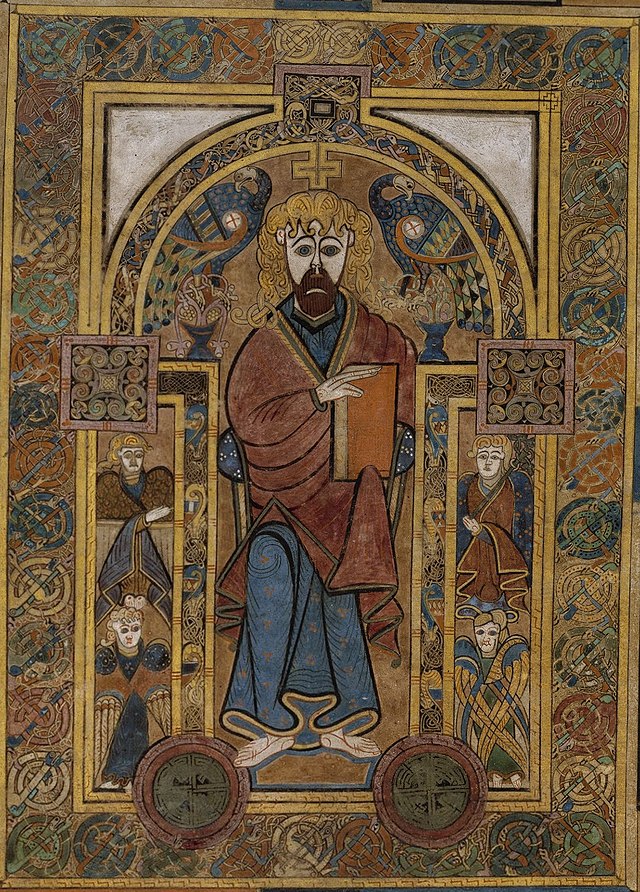

Consider Giotto Bondonne, born approx..1267, taught by the Italian artist Cimabue, known today as the father of the Renaissance. He always believed that art should be the handmaiden of the Church, but he also believed that art needs to be able to connect with the common man and his faith.

The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures, Giotto, 1315. Egg Tempera and Gold leaf

Giotto is famous for the Peruzzi Altar Piece, the Bardi Chapel, and Scrovegni Chapel fescoes, among much other sacred art. While the subject matter of his work was Scriptural, it had a strong bias towards depicting everyday life.

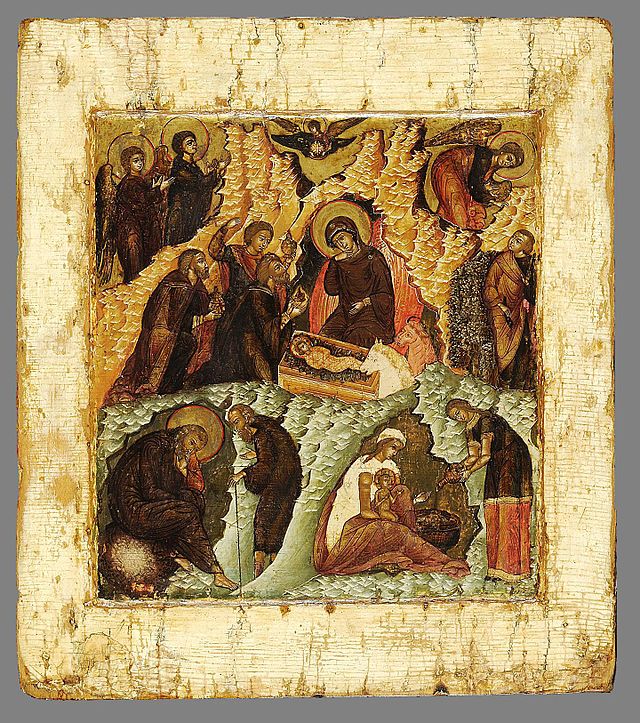

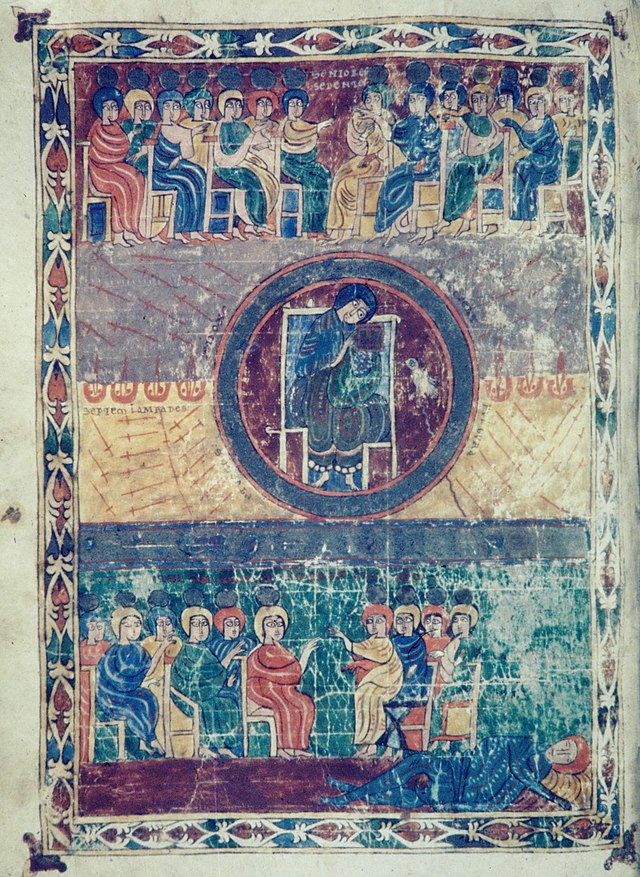

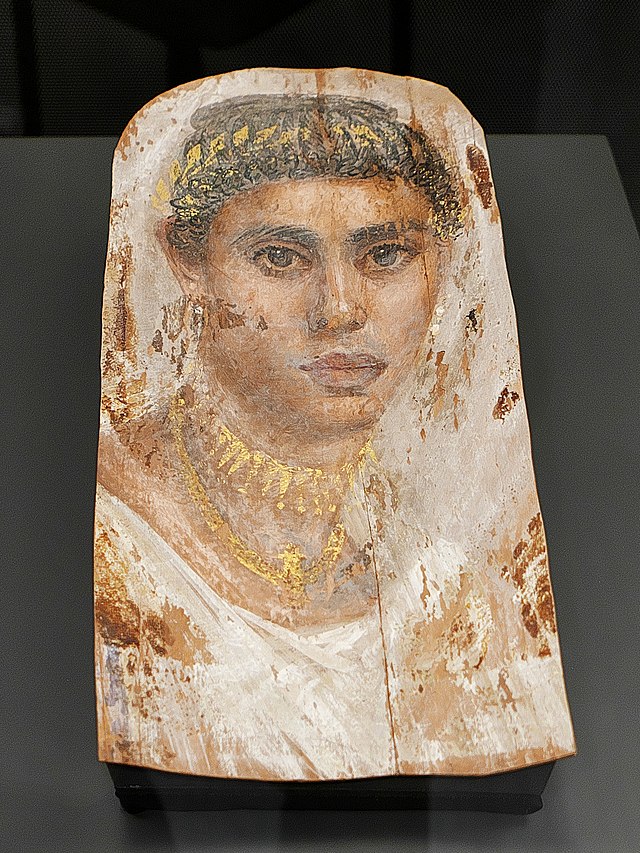

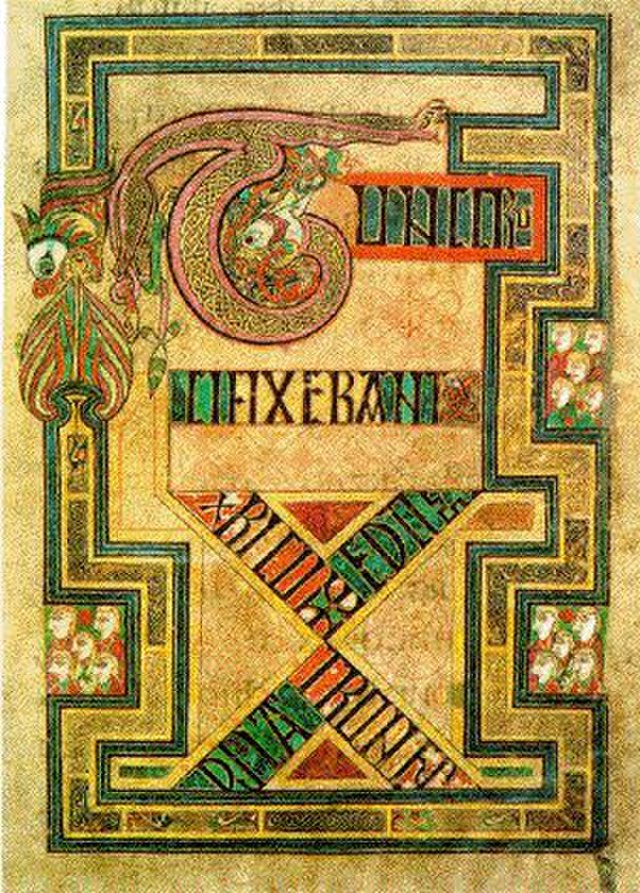

Byzantine art was prevalent even in Italy from the sixth century onward since Emperor Justinian brought craftsmen from Constantinople to build churches and monasteries. Some of these are still seen in San Vitale in Ravenna, San Marco in Venice and Monreale in Sicily. Giotto was influenced and informed by this Byzantine art as part of his early training.

During his lifetime, Giotto was heralded as an artist who revived the art of painting, which some felt had fallen into ruin over the course of the Middle Ages. He was famous for painting on a monumental scale, demonstrated by his majestic frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

Giotto…”brought back to light an art which had been buried for centuries…So faithful did he remain to Nature…that whatever he depicted had the appearance, not of a reproduction, but of the thing itself, so that one very often finds, with the works of Giotto, that people’s eyes are deceived and they mistake the picture for the real thing.”

Giovanni Boccaccio, a contemporary of Giotto

One of the main stylistic differences from Byzantine art that Giotto introduced was depicting the human form as it appears in nature. The figures appeared more natural and showed human expressions appropriate to the depicted scene.

The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures, Giotto, 1315. Egg Tempera and Gold leaf, detail

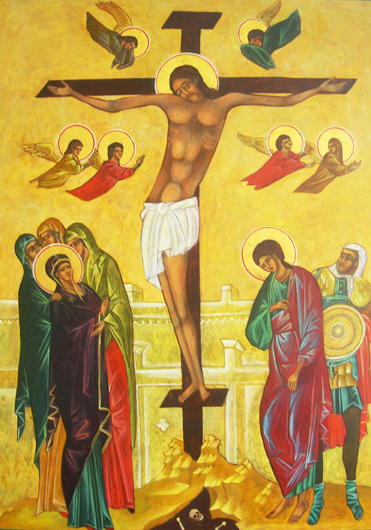

I understand that as Iconographers, we are taught to avoid this kind of naturalism in favor of stylized , expressionless figures on a flat surface. So what is my point? Only that it is possible to introduce artistic innovations into church art in order for that art to reach the common man.

Neon Artist , Stephen Antonakos, Icons

Here are a couple of”icons” created in 1989 that incorporate gold leaf, wood, light, and theology. Compare these with Giotto and they seem to apply more to a Byzantine definition of icon than Giotto’s religious art and those of the Renaissance that followed. And yet, Antonakos’s icons are entirely abstract. Do they relate better to our modern culture and create a holy image that brings God to mind?

“Transfiguration”. By Neon Artist, Stephen Antonakos 1989. Neon, Gold Leaf on Wood

Saint Peter Icon. by Neon Artist, Stephen Antonakos. Neon, gold leaf on wood, 1989

INNOVATION AS A WAY TO ENGAGE THE VIEWER

How do we innovate within a Byzantine Iconographic context today at a time when art making is so widely diverse and even technological? I don’t have any answers, except to say that it is a worthy challenge for iconographers and religious painters today!

Saint Nicholas. Todor Mitrovic

I’d like to close with another quote from one of my favorite contemporary Iconographers, Todor Mitrovic:

“In my opinion, church art, approached through its liturgical perspective, must be brought to life by people in actual time. This also means it must be brought to life in an actual cultural context – comparable with, but – at the same time – incomparable with, previously existing cultural contexts.

We are invited to transform this actual cultural context however impossible it may seem.

It is not expected of us to express the faith of people who once lived on the land we inhabit today, but instead – our own faith.

No matter how primitive and rudimentary our expression is, it has to be done from the heart, through the mind and body, otherwise we are avoiding the responsibility of being part of the Body of Christ. Such expression is part of our attempt to make the Body of Christ present, which is, when speaking about art, making it visible in a material and cultural context. This is why all we can give, all our talent, must be included in the process – otherwise we are denying our skill, burying talents to the ground (to use the Gospel parable), and at the same time doing little more than telling pleasant stories about the Middle Ages.”

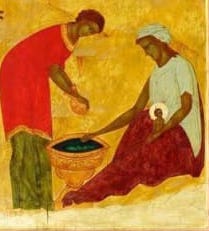

Joan of Arc, Christine Hales

May this article serve as both a challenge and an encouragement for each iconographer, urging us toward exploration, experimentation, and a celebration of diverse styles within contemporary iconography. Let the love of Christ infuse every stroke of our brushes and guide our collective journey as a group of artists profoundly devoted to Christ.

Christine Simoneau Hales

New Christian Icons My Patreon Page

Sources for this article:

https://www.getty.edu/news/everyones-talking-about-giotto/

Antonakos , by Irving Sandler

“