Books and Inspiration to Enrich Your Icon Writing Practice

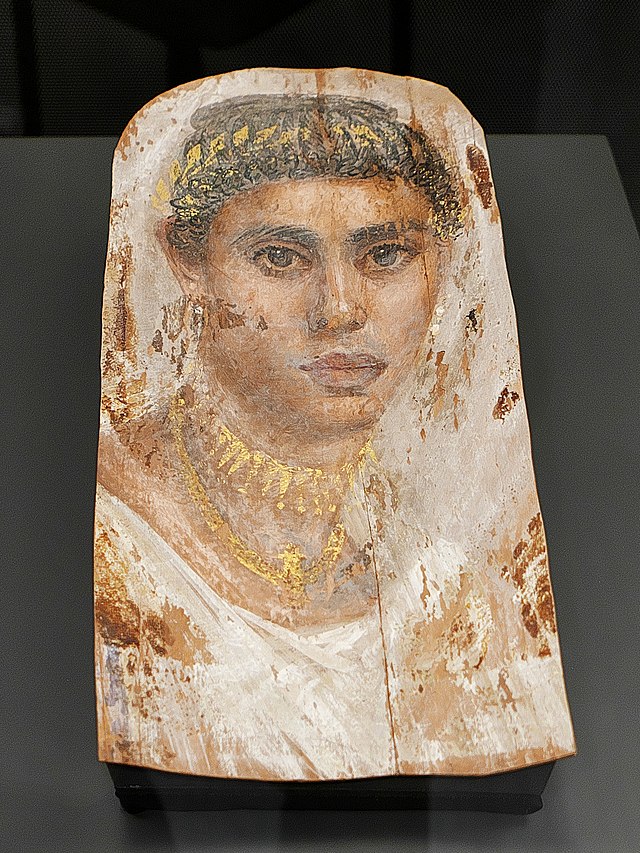

Summer unfurls like a painted scroll—light streaming through open windows, quiet hours stretching across the day, and, for the iconographer, a rare invitation to rest, reflect, and replenish the wellspring of inspiration. Whether you are a seasoned writer of icons, a beginner who has just dipped their brush into the egg tempera, or simply a lover of sacred art, the summer months offer an ideal time to step back from the demands of daily creation and immerse yourself in the wisdom, history, and spirituality that underpin the venerable and holy tradition of iconography.

Why Read in Summer? The Sacred Pause

In the stillness of summer, reading becomes a sacred pause—a time to deepen your understanding of icons not just as objects of devotion, but as living prayers in color and line. Iconographers often speak of their art as an act of contemplation: every stroke is a prayer, every layer a meditation. So too can reading be a contemplative act, enriching the mind and spirit while opening new vistas for creativity.

Foundational Texts: Revisiting the Roots

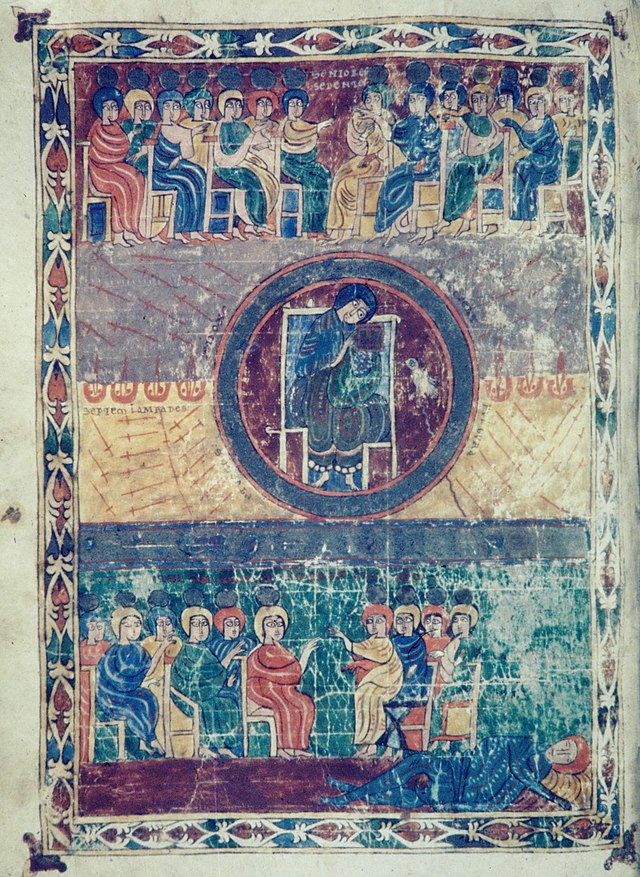

- The Meaning of Icons by Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky. This classic introduces the theological, spiritual, and artistic foundations of iconography. Through its pages, readers are led to understand the icon as a window to the divine, a theology in pigment, and a bridge between heaven and earth.

- Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church by Alfredo Tradigo. Tradigo’s compact yet richly illustrated guide offers both historical context and practical wisdom. Each page is a pilgrimage through time, introducing saints, feasts, and the symbolic language of orthodox sacred art.

- Icons as Communion by George Kordis. Kordis brings the ancient tradition into the present, with notes and observations on the drawing stages in icon painting. Amazon Link

- Orthodox Icon Patterns, Patterns and sketches for Iconographers: This is the revised version of Patterns & Sketches for Iconographers, with added content and additional patterns. A valuable resource for iconographers, this book contains a wide variety of patterns and sketches. Content including; icon patterns of the Nativity, the Theotokos, archangels, male and female saints, as well as halo patterns and 2 beautiful crucifixion crosses. Buildings and fabric/ background designs and icon borders. Each pattern is accompanied by color recommendations which are meant as a general guide allowing for adjustments due to differences in color names between pigments used with egg tempera and acrylic paints. (There is also a Volume II if you like this one.). Amazon Link

Summer Reads For Inspiration and Insight

Summer reading need not always be heavy with theory or thick with history. Sometimes, lighter fare—biographies, memoirs, and even novels—can kindle the imagination and nurture the soul of the artist. You might consider adding a few of these to your summer list:

- Praying with Icons by Jim Forest. Accessible and warmly written, Forest’s reflections on the role of icons in prayer lift the heart and draw the reader into a deeper appreciation of how icons shape and are shaped by the life of faith.

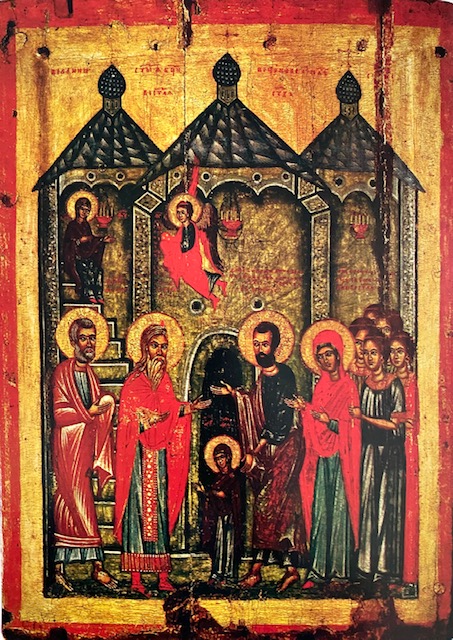

- The Mystical Language of Icons by Solrunn Ness. Nes explores in depth a number of famous icons, including those of the Greater Feasts, the Mother of God, and a number of the better-known saints, enriching her discussion with references to Scripture, early Christian writings, and liturgy. She also leads readers through the process and techniques of icon painting, showing each step with photographs, and includes more than fifty of her own original works of art. Amazon Link

- And if you would enjoy a deep dive into the life of the Blessed Mother Mary, I recommend “The Life of the Blessed Virgin” from the visions of Ann Catherine Emmerich, Incredibly revealing and edifying background of Our Lady, her parents and ancestors, St. Joseph, plus other people who figured into the coming of Christ. also available on Amazon: Amazon Link

- And also “True Devotion to Mary” by Louis de Montfort: Considered by many to be the greatest single book of Marian spirituality ever written, True Devotion to Mary is St Louis de Montfort’s classic statement on the spiritual way to Jesus Christ though the Blessed Virgin Mary. Amazon Link

- And last, but not least, is my own book on Icon writing, “Eyes of Fire, How Icons Saved My Life As an Artist”, with an appendix full of directions as well as an explanation of how modern art has been influenced by icons and how some of those principles can be used in present day icon creation. Amazon Link

As the art historian Roger Lipsky says in his book, “An Art of Our Own, the Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art”, “One of the tasks of the spiritual in art is to prove again and again that vision is possible; that this world, thick and convincing, is neither the only world nor the highest, and that our ordinary awareness is neither the only awareness nor the highest of which we are capable.”

And so my purpose in sharing this list of inspirational summer reading is to encourage you to engage with the ‘pause” of the longer summer days, and ponder on the beauty of nature and be open to glimpses of eternity that a fresh perspective can often foster. And then let this “higher”perspective inform your icon practice in the coming year,. In the words of Aidan Hart, in his book, “Beauty, Spirit, Matter, Icons in the Modern World, “The Icon invites us to see the world as God sees it.” With nature all around of us. may God bless us with His perspective and insights to carry forward into our work.

Until next month,

Christine Simoneau Hales, Iconographer/artist

My Websites:

- https://newchristianicions.com my main website

- Https://christinehalesicons.com Prints of my Icons

- https://online.iconwritingclasses.com my online pre-recorded icon writing classes

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK2WoRDiPivGtz2aw61FQXA My YouTube Channel

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristineHalesFineArt or https://www.facebook.com/NewChristianIcons/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christinehalesicons/?hl=en

- American Association of Iconographers: FB Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/371054416651983

- American Association of Iconographers Website: https://americanassociationoficonographers.com