Inspired by Robin M. Jensen

Christian art has never existed merely to decorate sacred spaces or to please the eye. At its best, it has served the Church as a theological language—one that gives visible form to invisible truths and nurtures worship practices that are both spiritually vital and theologically rooted. In The Substance of Things Seen, Robin M. Jensen articulates with clarity the indispensable role of art in Christian theology, worship, and communal life. Her insights are particularly relevant today as artists and iconographers seek to create contemporary icons that speak faithfully within modern contexts while remaining rooted in tradition.

Art as a Theological Practice

Christian art, and iconography in particular, occupies a unique place within the life of faith. Icons do not simply illustrate doctrine; they participate in it. They promote an ongoing conversation between faith and art—one in which visual form, prayer, and theology are inseparably linked. As Jensen reminds us, art within the Christian tradition is not neutral. It shapes belief, informs devotion, and forms the imagination of the worshiping community.

Yet this formative power carries responsibility. “If we remember that imitations are secondary things,” Jensen writes, “meant to guide us or inspire us toward the truth but not to substitute for it, we may avoid confusing objects with values or beautiful things with beauty itself.” The icon, then, is not an end in itself. It is a means—an invitation toward encounter rather than a replacement for the divine reality it signifies.

Icon Writing as Spiritual Formation

Within this framework, contemporary icon writing can be understood not simply as an artistic discipline but as a process of spiritual formation. Icon writing classes, when properly grounded, are aimed at producing visible images that point far beyond themselves. Creation and formation unfold together. The artist is shaped even as the image takes form.

This understanding resonates deeply with the Christian conviction expressed in 2 Corinthians 3:18: “We see not the truth itself, but are being transformed as we behold.” The thing we see is not the truth itself, but a means of encounter with the truth. In icon writing, the slow, prayerful process—layer upon layer of pigment, prayer, and contemplation—mirrors the gradual transformation of the human heart.

Seeing, Meaning, and Community

Jensen also reminds us that the perceived meaning of any work of art depends upon the experience, social location, interests, needs, and predispositions of its audience. Icons are not viewed in a vacuum. They exist within communities, cultures, and lived realities. Contemporary iconography must therefore attend carefully to context—not by abandoning tradition, but by allowing tradition to speak into the present moment with discernment and humility.

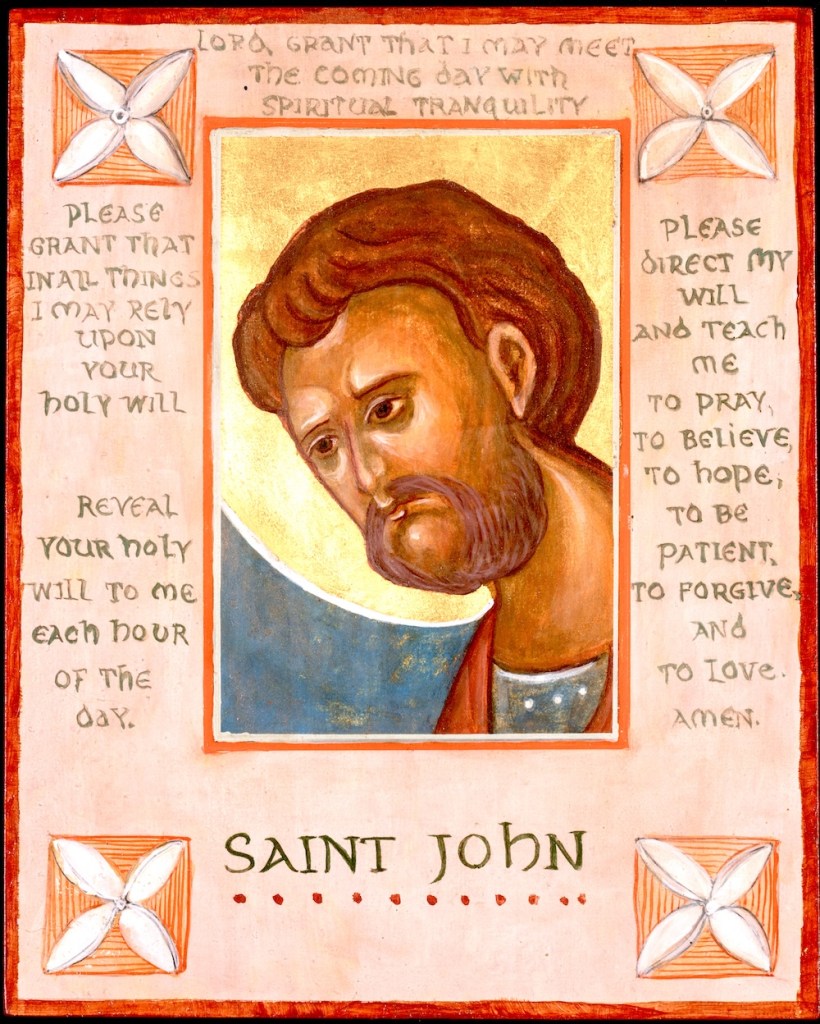

The icon does not record a particular physical appearance so much as it gathers and focuses prayer. It helps the viewer sense the invisible presence of the one to whom prayer is addressed. In this sacred exchange, the viewer does not merely look at the image but is invited to look through it. The icon serves as a medium of prayer directed toward a reality beyond the painted surface.

Holy Places and Sacred Spaces

This sacramental understanding of images naturally extends to architecture and sacred space. A holy place is traditionally understood as a meeting point between heaven and earth—a site where the divine presence has manifested, a gateway between the visible and the invisible. In this sense, all architecture functions iconically, and religious architecture does so in a particularly concentrated way.

Like painted icons, sacred spaces manifest ideas in nonverbal form, functioning symbolically at both the most mundane and the most profound levels. Depending on how it is viewed and used, a religious space may mediate or even “contain” holy presence in much the same way as a traditional icon painted on a wooden panel.

Toward a Faithful Contemporary Practice

Creating contemporary icons, then, is not about innovation for its own sake. It is about faithfulness—faithfulness to theological truth, to liturgical life, and to the formative power of sacred art within Christian community. Drawing on the wisdom articulated by Jensen, contemporary iconographers are invited to see their work not merely as aesthetic production, but as participation in the Church’s ongoing act of seeing, praying, and becoming.

In this way, the substance of things seen becomes a pathway toward the mystery of things unseen—and the icon remains what it has always been at its best: a window into divine presence, held in humility, reverence, and prayer.

Wishing you all a blessed and joyous New Year!

Christine Hales

Interesting Links for Iconographers:

Religious symbolism- Explained by Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/religious-symbolism History and symbolism of Iconography

History and symbolism of Iconography – Monastery Icons

Introduction to Icons: Patristix

Sacred Spaces: Richard Vosko, God’s House is Our House, Reimagining the Environment for Worship, Liturgical Press; and also by Richard Vosko. Art and Architecture for Congregational Worship: The Search for a Common Ground.