Ethiopian Orthodox Icon of Mary Feeding the Christ Child, 15th century

Holy work, writing/painting icons is both an art and a spiritual discipline. In both cases, there is no substitute for experience. The best teacher can only show the way, but the student must practice many, many hours, ask questions, and get feedback from the teacher and their community as the long process of icon training unfolds through the years. One must be always studying, learning, praying.

TEACHING

Even the best teachers don’t have time to teach the ethos, spiritual discipline, and spiritual worldview necessary within the context of an icon writing class. I constantly find myself trying to squeeze this into class sessions but there are always so many painting demonstrations and other topics needed to cover that there just isn’t enough time. For that reason, I am including some key concepts here in this month’s blog that I hope will be helpful and give the reader time to meditate, contemplate, and journal about them. Each individual iconographer will have their own areas of concentration and skills that need attention- there is no right or wrong answer, but instead the slow development of a spiritual mindset and worldview that will enhance one’s Godly service in this area.

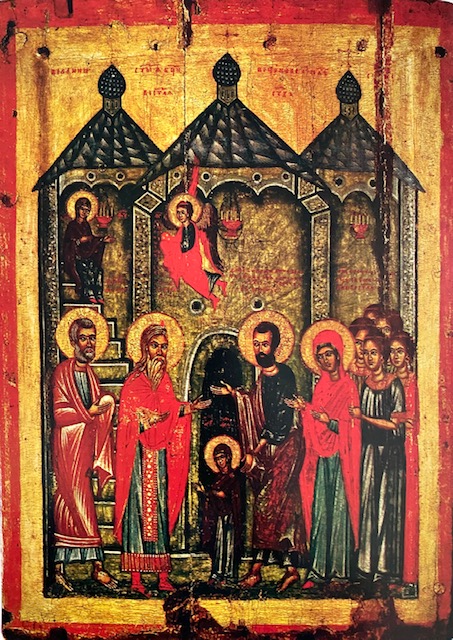

Russian Icon, 17th Century, Mother of God

Many of you are already familiar with the Divine Rules of an Iconographer, but I will include them here as they embody an ethos of combining love and work:

DIVINE RULES OF AN ICONOGRAPHER

• Before starting work, make the sign of the Cross; pray in silence and pardon your enemies.

• Work with care on every detail of your icon, as if you were working in front of the Lord Himself.

• During work, pray in order to strengthen yourself physically and spiritually; avoid all useless words, and keep silence.

• Pray in particular to the Saint whose face you are painting. Keep your mind from distractions, and the Saint will be close to you.

•When you choose a color, stretch out your hands interiorly to the Lord and ask His Counsel.

• Do not be jealous of your neighbor’s work; his /her success is your success too.

•When your icon is finished, thank God that His Mercy granted you the grace to paint the Holy Images.

• Have your icon blessed by putting it on the Holy Table of your parish church. Be the first to pray before it, before giving it to others.

• Never forget:

the joy of spreading icons throughout the world. the joy of the work of icon writing.

the joy of giving the Saint the possibility to shine through his/her icon.

the joy of being in union with the Saint whose face

you are revealing.

Saint Benedict Icon written by Christine Hales

WORK IS A HOLY GIFT

And so, our thoughts and attitudes while working are so important to the sacredness of the icon we are creating. “Each thought, each action in the sunlight of awareness becomes sacred. In this light, no boundary exists between the sacred and the profane.” Thich Nhat Hanh

Work is a holy gift. In his Rule, Saint Benedict states that all tools of the monastery are sacred and worthy of reverence. What are the sacred tools of the work we do?

“Just in the way the desert mothers and fathers reminded us that our cells can teach us everything, so can the work that we return to day after day be a place of inner transformation….As I listen for what the work needs at this stage and how it wants to come to birth in this world, I discover my own places which need releasing or ways to express my ideas with more clarity…Then consider whether it is possible for you to remember why you do the work. Can you do it out of love, recognizing that transformation occurs even there? Are there ways to bring love to things you find challenging and reframe them so that they rise like music and lift up your creative heart?” Christine Valtners Paintner , Abbey of the Arts.

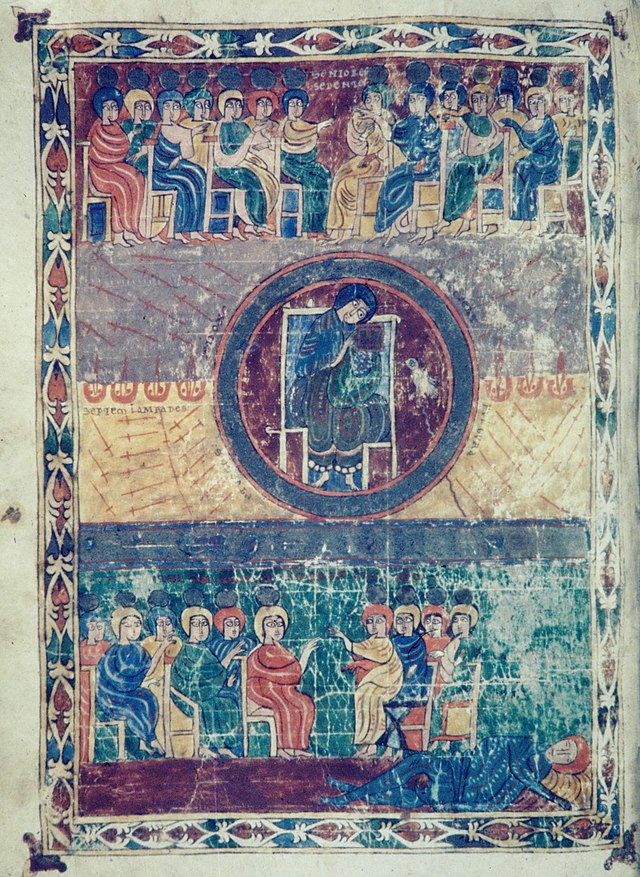

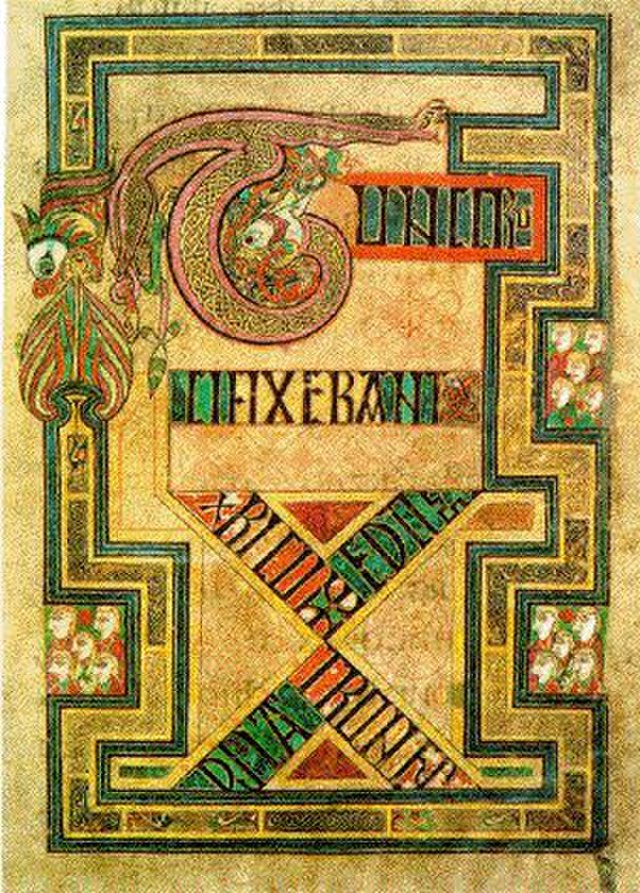

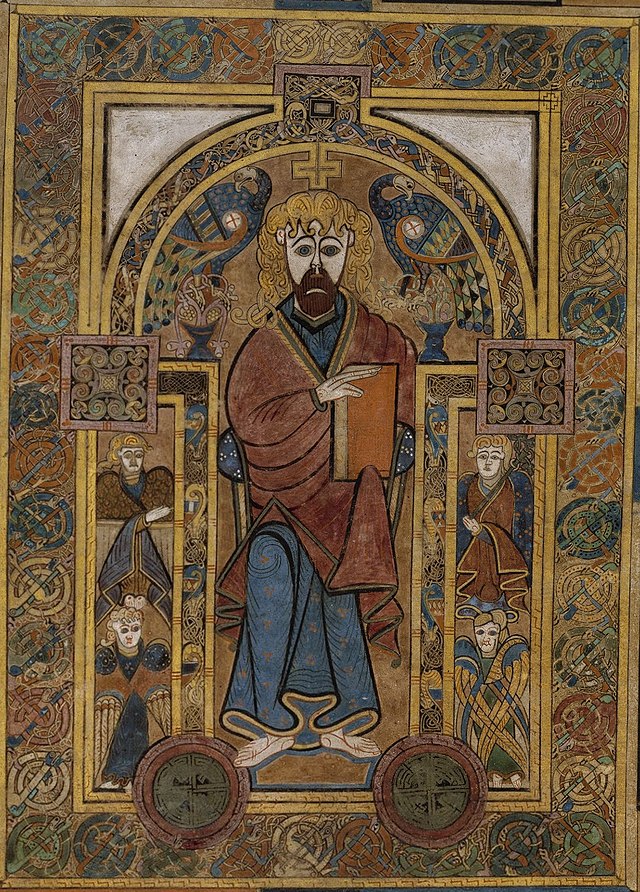

This and the image above, attributed to:Beatus, 9th century Illuminated Manuscript

I’ll close for this month with one more quote from Christine Valtners Paintner, Abbess of the virtual Abbey of the Arts, Ireland; “What difference would it make if you truly believed that your work makes a difference in the world, that the world needs what you have to offer…God invited each one of us in every moment to respond to our unique call.”

May God continue to bless the work of your hands, and hearts,

Christine Hales